Explosions Through Filtered Noise

An old-school algorithm for making sounds go kaboom.

This is a fun little algorithm described by David D. Thiel in the chapter Retro Game Sound: What We Can Learn from 1980s Era Synthesis in Audio Anecdotes, Volume I, edited by Ken Greenebaum and Ronen Barzel, published by A K Peters, 2003.

Filtered noise

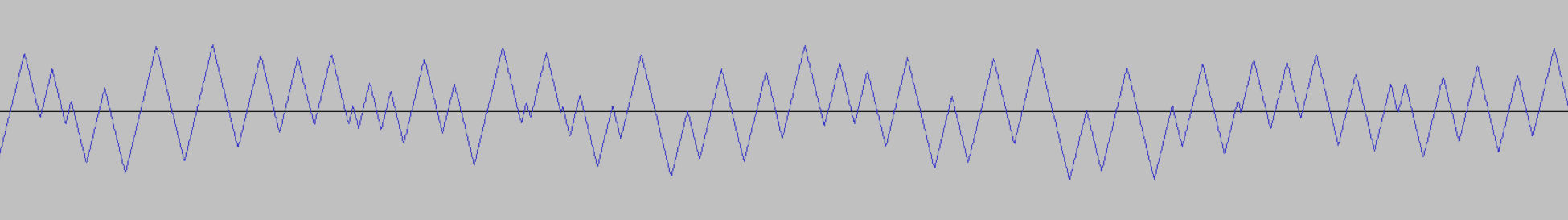

To make filtered noise, we can draw a waveform like in the following image where the slope between the points determines how much high frequency content is in the sound. Steeper slope = more high frequencies.

The waveform consists of connected line segments. The steepness of the line segments is fixed but their lengths are randomized. Another way to look at this algorithm is that it generates a triangle wave but at random times the direction changes.

When taken to the extreme, with a slope that is steep enough, this creates regular white noise. The shallower the slope, the more muffled the sound is — in other words, the more filtering is applied.

The original code as published in Audio Anecdotes was derived from assembly written for an 8-bit CPU. On a modern CPU with floating-point support it can be implemented like so:

struct FilteredNoise

{

FilteredNoise()

{

seed = uint32_t(time(nullptr));

target = random();

direction = 1.0f;

value = 0.0f;

slope = 0.0f;

}

void setCutoff(float frequency, float sampleRate)

{

slope = 3.0f * frequency / sampleRate;

}

float nextSample()

{

value += direction * slope;

// Time to reverse direction?

if (value * direction >= target) {

value = target * direction;

direction = -direction;

target = random();

}

return value;

}

private:

float random()

{

// Generate a pseudorandom number in the interval [0, 1).

seed = seed * 196314165 + 907633515;

return float((seed >> 8) & 0xFFFFFF) / 16777216.0f;

}

uint32_t seed; // for the random generator

float value; // current value

float slope; // speed by which the value changes

float target; // destination value (always positive)

float direction; // going up (1.0) or down (-1.0)

};

On every timestep, the nextSample() method increments the current sample value by the slope. When the value exceeds the target, the direction is reversed and a new target is picked using a random number generator.

If the previous target was above zero, the new target is below zero, and vice versa. On average, the waveform will be positive as often as it is negative, and there will be no DC offset.

In a frequency analyzer the noise looks like the following:

There is a clear 12 dB/octave roll-off like you’d see with a second-order low-pass filter. There is also a resonant boost around the cutoff point, here at 500 Hz. Where the cutoff frequency is located depends on the chosen slope.

This simple method creates noise that appears to be filtered.

However, if you create white noise in a tool such as Audacity and apply a 12 dB/octave low-pass filter, the filtered white noise sounds quite different. The sloped line segments method sounds a lot “rougher”.

The cutoff frequency

How does the slope relate to the cutoff frequency?

If we were to set slope = 4 * frequency / sampleRate and always have target = 1.0 rather than randomly choosing it, the algorithm creates a normal triangle wave. In the frequency analyzer this shows peaks at the fundamental frequency and for the odd harmonics.

The reason for needing the multiplier 4 is that slope describes how quickly the waveform’s amplitude rises from 0.0 to 1.0, and one period of the triangle wave is made up of four such line segments (0 → 1 → 0 → –1 → 0).

Nitpicking: If you examine the triangle wave made by this method in the frequency analyzer, you’ll notice the fundamental doesn’t show up exactly on the chosen frequency. The reason is that the triangle wave is not 100% clean because of the line value = target. This clamps the value when it overshoots the target, making the period slightly longer than it ought to be, and the fundamental frequency slightly lower.

Why does this method cause filtered noise?

Since target can be randomly anywhere between 0.0 and 1.0, it doesn’t generate a regular triangle wave but merely something triangle-ish with a period that is constantly changing. This adds noise around the harmonics.

The signal appears filtered because the triangle-ish harmonics roll off in the same way as a second-order low-pass filter, by 12 dB/octave. The “resonant peak” around the cutoff frequency is simply the fundamental sticking out above the noise level.

Because the noise signal has a smaller period on average than a regular triangle wave, the cut-off frequency will appear higher. To compensate for this, the multiplier in the equation in setCutoff() is not 4 but 3. This is not exactly right, but close enough.

This formula for setting the slope works pretty well for low cutoff values, say anything below 10 kHz. For higher cutoffs, the slope becomes imprecise because at high frequencies there are only a few samples per cycle and the waveform ends up alternating between 1 and 2 samples per line segment.

Just for fun, instead of making target go randomly between 0.0 and 1.0, we can also keep it closer to 1.0. This produces a blend between the noisy sound and a regular triangle wave.

const float mix = 0.3f;

target = (1.0f - mix) + random() * mix;

The smaller the mix value is, the less randomness there is in the signal and the more “pitchy” the sound becomes, which creates an interesting type of noise in its own right. Using mix = 0.3 clearly shows that the noise is added around the harmonics from the triangle wave and that is what creates the shape of the filter roll-off.

Explosions!

To create an explosion, most of the algorithm stays the same, except we now gradually decrease the slope whenever the waveform changes direction. This is like doing a high-to-low filter sweep.

struct Explosion

{

Explosion()

{

seed = uint32_t(time(nullptr));

target = random();

direction = 1.0f;

value = 0.0f;

slope = 0.0f;

slopeDecrement = 0.0f;

slopeEnd = 0.0f;

}

void start(float sampleRate)

{

slopeDecrement = (random() + 0.5f) / sampleRate;

slope = slopeDecrement * 250.0f + random() * 250.0f / sampleRate;

slopeEnd = 20.0f / sampleRate;

}

float nextSample()

{

// Gently ramp back to the center when done.

if (slope < slopeEnd) {

if (direction * value >= 0.0f) { // finished?

return 0.0f;

} else {

value += direction * slopeEnd / 4.0f;

return value;

}

}

value += direction * slope;

// Time to reverse direction?

if (value * direction >= target) {

value = target * direction;

direction = -direction;

target = random();

slope -= slopeDecrement;

}

return value;

}

private:

float random()

{

// Generate a pseudorandom number in the interval [0, 1).

seed = seed * 196314165 + 907633515;

return float((seed >> 8) & 0xFFFFFF) / 16777216.0f;

}

uint32_t seed; // for the random generator

float value; // current value

float slope; // speed by which the value changes

float target; // destination value (always positive)

float direction; // going up (1.0) or down (-1.0)

float slopeDecrement; // speed of filter sweep

float slopeEnd; // when to stop

};

The start method randomly chooses the initial slope to make every explosion slightly different. The rate at which the slope changes, slopeDecrement, is also randomized.

The values used here were derived from the original implementation and correspond approximately to an initial cutoff frequency between 40 Hz and 200 Hz, and an explosion length between 2 and 8 seconds.

Once the slope has become small enough, determined by slopeEnd, the explosion is done. To avoid a DC offset, the code does a linear ramp back to 0.0 and then stays there.

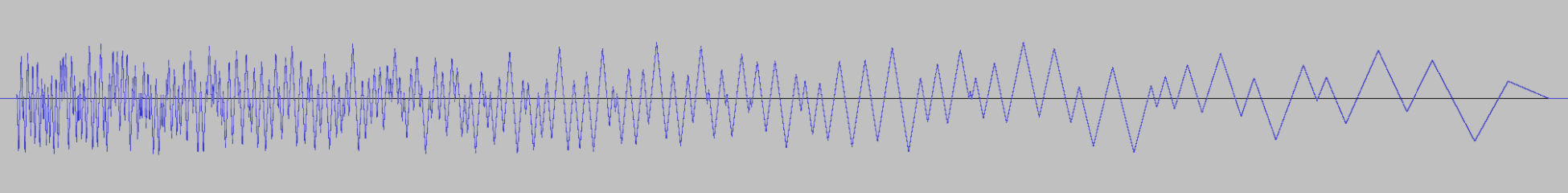

The generated waveform looks like this:

What it sounds like:

The explosions sound kind of cool at the rather low sampling rate of 5 kHz used by the original article. These sound effects were intended to be played on arcade cabinets and would have made a nice rumble. But at 44.1 kHz and on hi-fi loudspeakers, it doesn’t make for very realistic explosions. Still, it’s a pretty clever algorithm that shows you can do a lot with a little!

Experiment with different values for slope and slopeDecrement to make other sound effects, such as thunder, drums, and wind.